by the Hospital Senses Collective

‘[In] my early days in the Fund (1937) … we were taken to Guy’s by old Sir Cooper Perry and there outside the dispensary we met a long row of miserable looking citizens queuing up. One old gent was seized by the shoulder by Sir Cooper, who turned him round briskly and said, “You like waiting, don’t you?”. The horrified man replied “Oh yes sir, yes sir, yes sir!”. Whereupon Sir Cooper turned to the King’s Fund delegation and said “You see, they like waiting.” ‘ Letter from R. E. Peers to W.J.H. Butterfield, 1965 [1]

We may no longer need to turn up and queue at hospitals, but watching the clock is an experience shared by most patients and visitors in hospitals. For patients in particular, a period of waiting is typically expected at a hospital, taking the form of a so-called ‘enforced pause’.[2] When waiting, the relationship between the spatial and temporal is particularly apparent; the physical environment and atmosphere in which one waits is significant.

The specific sensory features of the waiting room are shaped by this temporality. As Harold Schweizer suggests, ‘time must suddenly be endured rather than traversed, felt rather than thought. In waiting, time is slow and thick’.[3]

The spaces of waiting then are perhaps the opposite sensory experience to the corridor: static, slow, immersive.

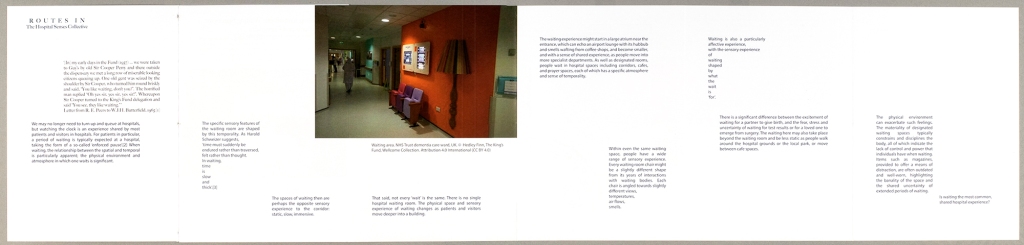

That said, not every ‘wait’ is the same. There is no single hospital waiting room. The physical space and sensory experience of waiting changes as patients and visitors move deeper into a building.

The waiting experience might start in a large atrium near the entrance, which can echo an airport lounge with its hubbub and smells wafting from coffee shops, and become smaller, and with a sense of shared experience, as people move into more specialist departments. As well as designated rooms, people wait in hospital spaces including corridors, cafes, and prayer spaces, each of which has a specific atmosphere and sense of temporality.

Within even the same waiting space, people have a wide range of sensory experience. Every waiting room chair might be a slightly different shape from its years of interactions with waiting bodies. Each chair is angled towards slightly different views, temperatures, air flows, smells.

Waiting is also a particularly affective experience, with the sensory experience of waiting shaped by what the wait is ‘for’.

There is a significant difference between the excitement of waiting for a partner to give birth, and the fear, stress and uncertainty of waiting for test results or for a loved one to emerge from surgery. The waiting here may also take place beyond the waiting room and be less static as people walk around the hospital grounds or the local park, or move between cafe spaces.

The physical environment can exacerbate such feelings. The materiality of designated waiting spaces typically constrains and disciplines the body, all of which indicate the lack of control and power that individuals have when waiting. Items such as magazines, provided to offer a means of distraction, are often outdated and well-worn, highlighting the banality of the space and the shared uncertainty of extended periods of waiting.

Is waiting the most common, shared hospital experience?

References

- London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), London, Guy’s Outpatient Survey, A/KE/I/01/03/001.

- R. A. Kearns, P. M. Neuwelt, and Kyle Eggleton. ‘Permeable Boundaries? Patient perspectives on space and time in general practice waiting rooms’, Health & Place, 63 (2020).

- H. Schweizer, On Waiting (Routledge, 2008), p. 2.

NEXT PAGE: CLOCKS, or return to full WAITING SPACES booklet.